|

TopNax |

|

Home†††††† Previous††††††† AMD page†††††††† Intel page†††††††† Next |

Benchmark Results: Productivity

|

|

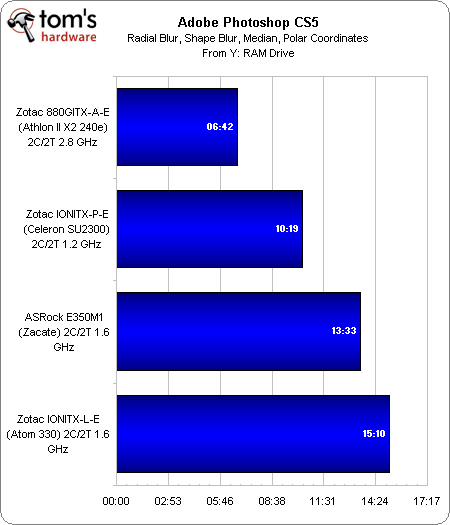

Our threaded Photoshop CS5 test definitely favors the low-power Athlon II. Intelís Celeron SU2300 also fares well, followed by AMDís E-350. The Atom/Ion combination brings up the rear.

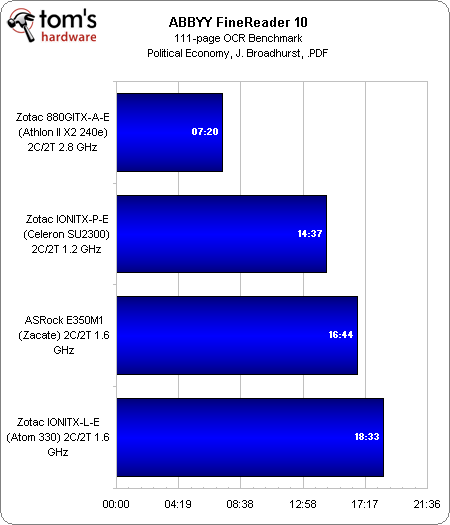

If ASRockís E350M1 is part of a productivity-oriented machine, then itís feasible that itíll need to interact with a scanner and OCR software. Naturally, AMDís desktop architecture reigns supreme here. But the Celeron, E-350, and Atom all fall within four minutes of each other (a veritable lifetime in the world of high-end CPUs, but relatively less in the power-optimized market).

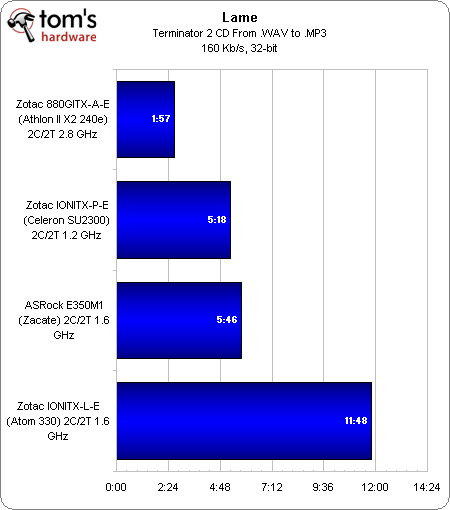

Converting a WAV file to MP3 is another fairly realistic usage case for a low-power system. And what we see here is interesting. Lame is not threaded, so itís certainly not surprising to see the 2.8 GHz processor tearing things up. More surprising is that Intelís efficient Celeron SU2300 takes second place, with its 1.2 GHz clock. The E-350 is right behind, running at 1.6 GHz. And the Atom, with its in-order execution pipeline gets far less done at the same 1.6 GHz clock rate. This is a result youíll see againóso keep in mind that Atom really needs the parallelism enabled by a second core and Hyper-Threading to fully maximize its performance.

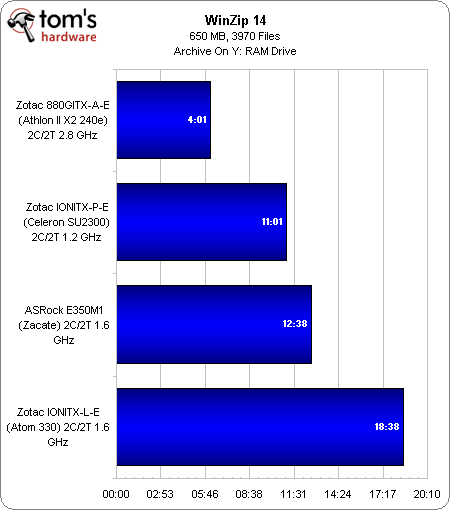

The same issues trouble Atom here in WinZip, which also isnít threaded. The 1.6 GHz processor struggles to get the workload completed compared to AMDís E-350, which runs at the same clock rate, but employs a more performance-oriented architecture. In fact, the Zacate APU is only a minute and a half slower than the 1.2 GHz Celeron SU2300, based on Intelís Core 2 microarchitecture.

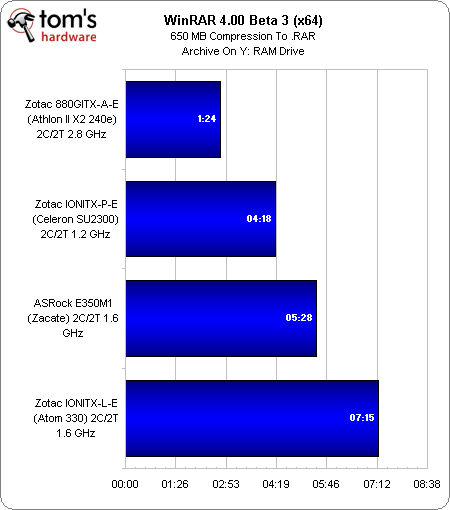

WinRAR is able to take advantage of processors with multiple cores, and the Atomís loss isnít as pronounced. Again, AMDís desktop architecture takes the top spot, following by Intelís 10 W Celeron, the E-350, and Intelís Atom 330.

|

Benchmark Results: Productivity |

Benchmark Results: Media Encoding |

|

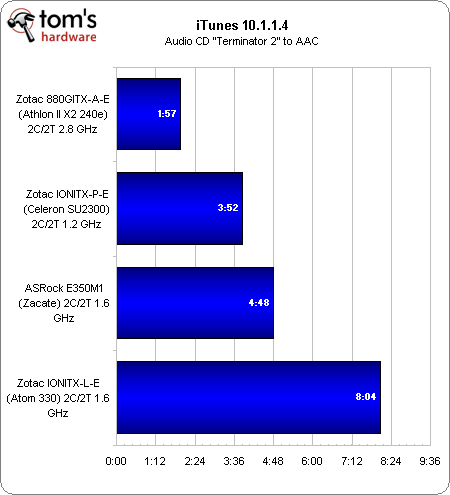

Not surprisingly, the desktop-class Athlon II, running at 2.8 GHz, finishes this test the fastest. Itís followed by Intelís 10 W Celeron SU2300. The E-350 takes a third-place spot not far behind, and Intelís Atom brings up the rear way back there. Of course, iTunes is single-threaded, so we can see just how badly AMDís Bobcat core beats Atom on a clock-for-clock basis (weíre talking one 1.6 GHz core per processor here).

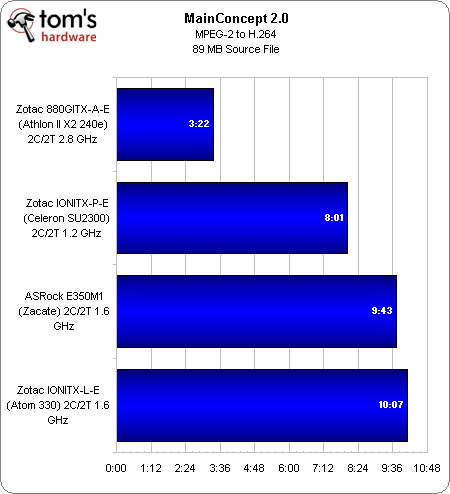

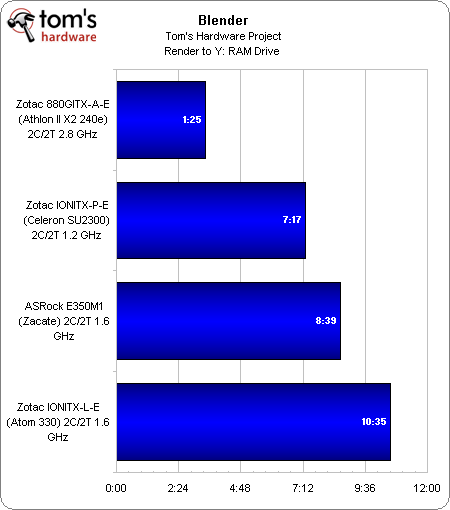

Itís probable that most folks arenít going to push a lightweight system based on E-350, Celeron SU2300, or Atom 330 any harder than an iTunes encode. But we wanted a closer look at threading performance, and MainConcept is able to provide that. The performance story is indeed much different here, since Atom includes two cores and Hyper-Threading support. Instead of the blowout seen in iTunes, ASRockís E350M1 is just barely able to scrape by the IONITX-L-E. Then again, remember the Atom board still costs $190 compared to the Brazos platformís $110 or so. Even if you factor in the benefit of onboard Wi-Fi from Zotac, youíre still getting a lot more performance for your money via Brazos.

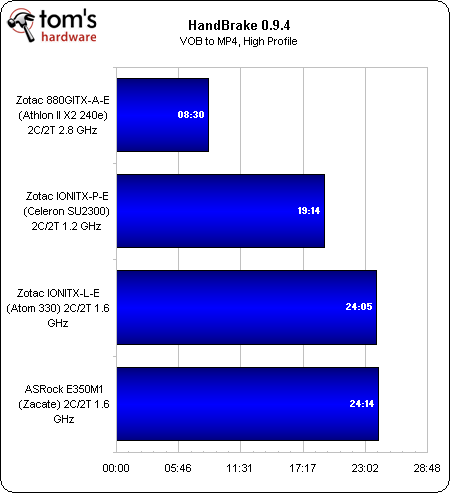

Here, Intelís Atom processor actually manages to sneak past AMDís E-350. With that said, if youíre doing heavy lifting in HandBrake, itís likely worth spending money on a separate motherboard and desktop processor, rather than trying to get mobile architectures to do that job. Even the low-power Athlon II is 285% faster than AMDís E-350.

This really goes without saying, but if youíre expecting to run desktop-class workloads, you shouldnít show up with a mobile-oriented processor. The Athlon II X2 240e simply mops the floor with the three other contenders here. |

Power Consumption And Pricing |

|

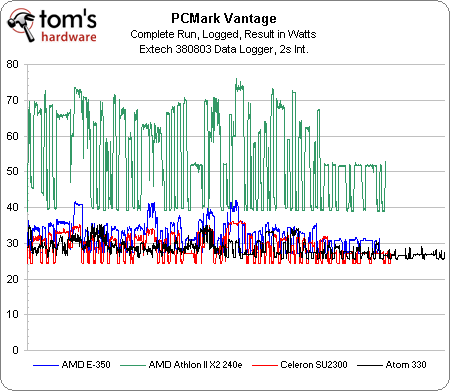

Power is where our performance numbers get put into context. Remember, I threw a pretty wide net here, looking for the best way to quantify what AMDís Brazos platform could do.

∑ I used a low-power desktop processor with integrated Radeon HD 4250 graphics for the folks wondering just how much better one of AMDís current 45 W parts perform. Thereís also the comparison between Radeon HD 4250 and Radeon HD 6310. ∑ I used a Celeron SU2300-based Mini-ITX board with Ion graphics for the folks whoíre already using Intelís ultra-low voltage mobile processors on the desktop. Thereís also the comparison between Radeon HD 6310 and Ion. ∑ I used an Atom 330-based Mini-ITX board with Ion graphics because Atom is E-350ís natural competition. Remember that the dual-core 1.6 GHz Atom 330 isnít much slower than the newer Atom D510 at 1.66 GHz, and the pounding Atom takes here isnít going to be mitigated by an incrementally faster clock and more efficient platform architecture.

AMDís E-350 is actually more power-hungry than Intelís 10 W Celeron SU2300 and 8 W Atom 330. No surprise there. But the average power numbers separate all three platforms by less than 4 W. Now, yes, the two Intel-equipped boards have Wi-Fi cards. But you also have to remember that theyíre armed with Nvidiaís Ion chipset, while the E350M1 uses AMDís A50M ďHudsonĒ FCH. Zacateís 18 W TDP includes graphics. This isnít the case for Celeron or Atom.

Interestingly Celeron uses more power under load and less power at idle than Atom. So, both Intel-based platforms average about 28 W across the PCMark Vantage run. The Zacate-based setup averages 32 W.

Pricing Now, when you look at the power chart and the PCMark Vantage benchmarks, the Celeron/Ion combo would seem to have a modest advantage over AMDís latest and greatest. But then you have to take pricing into consideration. Zotacís IONITX-P-E currently sells for about $200. Its Mini PCI Express card can be found for roughly $20, so weíll call that $180 for the motherboard and processor. ASRock is planning to sell the E350M1 for $110. Thatís 61% of the Celeron boardís price, even if you factor out the wireless module. The E350M1 offers better gaming performance too, thanks to its Radeon HD 6310 graphics. Ion simply canít keep up. Comparing AMDís Zacate APU to Atom is even easier. Youíll pay $190-ish for the IONITX-L-E, and it too includes wireless networking. In every discipline, the Brazos platform destroys it, including (and especially) price. The only compromise is a <4 W average power consumption disadvantage across a PCMark Vantage run. The desktop platform I built was more anecdotal than anything. We already knew its performance would far exceed E-350, as would its power use. The price is up there, too, though. The 880GITX-A-E sells for $115 on its own, while the Athlon II X2 240e sells for $75 or so. At the same time, with those numbers in mind, an 880G-based Mini-ITX setup is actually your best bet for performance/$, so long as your enclosure is capable of handling the higher power numbers. The Zotac board doesnít offer PCI Express expansion, so its options are limited in a gaming context, but Blu-ray movies play back smoothly thanks to the integrated GPUís UVD2 logic. |

Conclusion |

|

So, thereís a lot of talk about what Fusion is and how APUs are going to change the face of computing. AMDís own Rick Bergman, senior vice president and general manager of AMDís products group, went out on a fairly long limb at this yearís CES by saying: ďWe believe that AMD Fusion processors are, quite simply, the greatest advancement in processing since the introduction of the x86 architecture more than forty years ago. In one major step, we enable users to experience HD everywhere as well as personal supercomputing capabilities in notebooks that can deliver all-day battery life. It's a new category, a new approach, and opens up exciting new experiences for consumers.Ē The greatest advancement in processing since x86 was introduced? While we undoubtedly haven't seen as many top-secret projects as Rick, the Zacate APU we have on hand definitely doesn't deserve that sort of pat on the back. Now, according to AMDís numbers, its ďall-dayĒ result is actually 11 hours of runtime on an E-350-based notebook with a 62 Wh battery sitting idle. Active, running 3DMark06, the platform purportedly achieves four and a half hours. Those certainly arenít bad figures if they carry over to shipping products later this quarter. But in the context of nettops based on ASRockís E350M1 and boards like it, weíre still dealing with a fairly basic concept here: Zacate is the combination of processor cores and graphics elements sharing a memory controller, similar to Intelís Atom-based Pine Trail platform, and indeed the Sandy Bridge processors that just launched a couple of weeks ago. Dress the technology up with new acronyms and sweeping initiatives, but the basic tenets distill down to this: integration is the key to higher performance, lower power consumption, and lower bill of materials in the mobile and mainstream desktop spaces. This is less about an earth-shattering vision and more about smart business. Weíre already seeing companies like CyberLink make focused optimizations based on the fact that graphics and execution cores now live on the same die, but we have to imagine AMD is hoping to see much more impactful development efforts in its Fusion-based products that pack more in the way of GPU muscle. We can only assume thatís still in the works. For now, the ramifications of Fusion-as-an-initiative are limited. What we do have are the benefits of integration and a new processor architecture from AMD. The company clearly looks to be going after Intelís Atom processor. Itís an easy target, given its ďgood-enoughĒ approach to computing. And indeed, the Brazos platform decimates Atom in single-threaded apps, still manages to beat it decisively in more parallelized programs, and embarrasses it in anything having to do with graphics. Once we start getting our hands on netbooks featuring Zacate and Ontario APUs, weíll get a better picture of how theyíll compare in price and longevity. On the desktop, Brazos goes up against more formidable competition (albeit pricier competition, too). The experience of using a Brazos-based machine is night-and-day better than a desktop with Intelís Atom. The Celeron SU2300 is an impressive little CPU, matched to Nvidiaís Ion chipset, and weíd have to call it comparable. AMDís Athlon II X2 is significantly faster, but you also incur completely dissimilar power consumption, too.

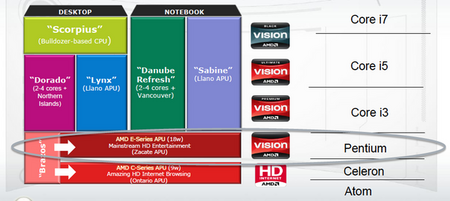

Unfortunately, this slide, which AMD presented back when it previewed Brazos, is entirely too optimistic. Zacate can go head-to-head against Intel's lowest-wattage Core 2-based Celeron processor, but I can't imagine it faring well against the Arrandale-based U3600, which runs at the same 1.2 GHz and costs the same $134. Even less likely is an even match-up against a Pentium-branded chip. In reality, I think AMD needs to shift the Intel column of the above slide up a notch to more accurately reflect its performance. Where Brazos cannot be beaten is price. ASRock anticipates selling its E350M1 for $110, and we hear that competing boards will go for $100. Buy a case, power supply, 4 GB memory module, and a mobile hard drive if youíre on a budget. Factor in a Blu-ray drive if you want it in the living room. Thatís a platform Iíd like to have as an HTPC or commons-area kiosk in the house. Had AMD been given a choice, I donít think it would have decided to use Zacate and Ontario as the springboards for heralding the arrival of Fusion. As fate would have it, though, weíll have to wait for the Sabine platformís 32 nm Llano APU (expected in Q2í11) for a better look inside AMDís plans for the future.

|

|

Home†††††† Previous††††††† AMD page†††††††† Intel page†††††††† Next |